The traditional process of kōji* malt production, sei-kiku (literally: make + kōji), takes place within what is known as the “kōji room” located on the climate-controlled second floor of the Matsumoto Sake Brewery. As the production of malt at the brewery is taking place during the colder months, climate regulation is crucial for the proper growth of their kōji, a prized mold used widely in food and beverage production in Japan.

*editor’s note: the name, kōji, is a synonym for a brewer’s mold and the malt product it produces.

Photo: Steam rising from the brewery in the morning of the beginning of spring

(taken at 6:45 am on February 3, 2021)

Even in modern times, sei-kiku is regarded as the most important step in sake brewing. Likewise, malt production in beer brewing is the most important step, strongly influencing its flavor. In the past, beer breweries had a dedicated malt factory on the same site, with specialists in charge of malt production being respected highly, second only to the brewery’s chief engineer.

The production process of brewed liquor begins with saccharification of a main ingredient and the conversion of starches into sugar. In beer brewing, barley is germinated, and the enzymes produced in the barley convert its carbohydrates into sugars that are later fermented by yeasts into alcohol. In sake brewing, the dai-shi (master) and/or kōji-shi (kōji expert), specialists in charge of the malt, spray a very small amount of Aspergillus oryzae (yellow kōji) spores onto steamed rice. The hyphae of the mold grows on and inside balls of rice (previously formed into shapes similar to rugby balls) producing and accumulating enzymes used in saccharification.

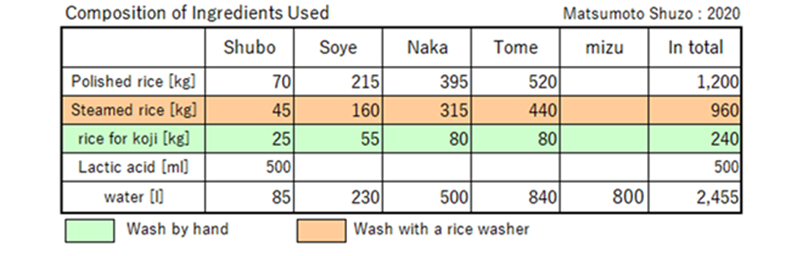

In this way, kōji mold is grown in the steamed rice, and the resulting product is known as kōji malt, or simply as kōji. Total produced kōji accounts for 20% of the total raw rice, and the remaining 80% becomes "kake" rice, which is saccharified by kōji mold enzymes and converted to alcohol.

Table: Composition of ingredients used in sake production

In the next part of this entry will be a detailed explanation of kōji mold, kōji production, and the kōji room.

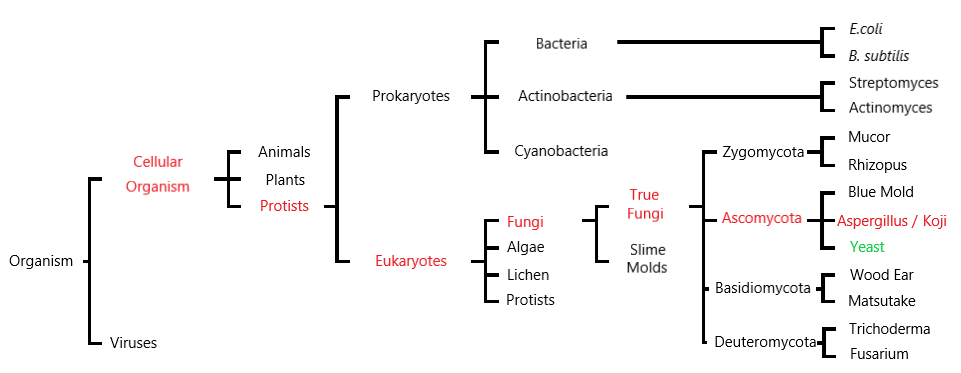

Biological Classification of kōji mold

Kōji mold is a eukaryotic organism, a hyphae-producing filamentous fungi falling under the true fungi classification and further divided into the ascomycetes group of organisms.

Characteristics of kōji include:

(a) oxygen is required for its growth

(b) it is vulnerable to drying and heat

(c) grows on the surface of damp substrates and penetrates into them with its hyphae

(d) it is a heterotrophic feeder that produces enzymes to break down proteins, fibers,

and sugars from organic matter for its nourishment

Kōji production

The kōji production process described here refers to the solid kōji used for sake production, which is made by spraying steamed polished rice with spores of yellow aspergillus.

Firstly, a brief history of kōji production:

Kōji was originally made by the "bed kōji method", a method whereby kōji was spread upon woven straw matting. This was done twice a year during the equinoctial week in both spring and autumn, particularly suitable times for its production.

With advances being made in cold season sake production, a method of kōji production using "small lid kōji " (up to 1.5kg of rice put into small shelf-like vessels) was implemented throughout the Edo period. However, the method needed a dedicated kōji room and considerable manpower to facilitate it.

"Large box kōji " (boxes now carried 15kg of kōji) methodology was later implemented, allowing for an increase in production scale and, from a labor point of view, improve the rationality of operations.

Differences between the "bed kōji", "room lid kōji", and "box kōji" methods

In the bed kōji method, steamed rice is spread onto cloth-lined rice straw mats which have been placed on a dirt floor. The rice is then bundled up in the sheets of cloth. The rice does not need to be artificially seeded (i.e. with sprays containing the conidia of yellow aspergillus), as the rice is inoculated naturally.

Photo: the work of bringing steamed rice into the kōji room is called "pulling in"

(photo taken at 7:50am, January 31, 2021)

Later innovations to the method included spreading steamed rice onto tables within a " kōji room". The rice was periodically spread thinner, and in doing so, released heat from the inner layers of rice to the room, which served as a means to regulate temperature in the room for optimal kōji development.

Current kōji production methods involving mechanical ventilation, can be regarded as an advanced version of this method. Nowadays, sterile air is alternately passed between lower and upper layers of the kōji, and its temperature is controlled with aid of the latent heat of vaporation. This has allowed for the production of large amounts of kōji over shorter periods.

The "room lid kōji" method is also known as the "small box kōji" method, whereby 1.5 kg of kōji is stored in a small box made of stripped cedar. Temperature control was challenging, as it involved heating and maintaining the temperature of multiple boxes in one whole group (rather than individually). In the olden days, room insulation was difficult to manage sufficiently, so the periods for growing kōji were separated into a bed stage and a shelf stage, and it was logical at the time to operate in a way that ensured that the temperature of the kōji product was managed in line with that of the kōji room.

Photo: Steamed rice is seeded with kōji starter, and bundled up after a good mixing through.

This is the first half of the kōji production process, and is named the "floor period".

(8:20am, January 31, 2021)

In the "bed kōji" and the "box kōji" methods, temperature is controlled by using the latent heat of vaporization on the kōji surface, which spreads out horizontally. In a different method, the "room lid kōji" method, a number of small boxes are stacked vertically upon each other to form a block, which allows for easy maintenance of temperature. The small boxes are periodically moved up and down the stack, and the temperature of the boxes are controlled by the latent heat of vaporization coming off the kōji surface. When it came time to judge the quality of the kōji, it was only necessary to check one box per stack as this reliably indicated the quality of the block, which was convenient.

The "room lid kōji method" was once the golden standard for kōji production, though results differed depending on how skilled staff were at stacking and moving the boxes. Less experienced workers may move boxes less efficiently which can compromise temperature control and thus quality of the kōji. These days, kōji lid manufacture is difficult owing to a lack of good cedar stripping board, and this is the biggest roadblock in producing kōji from box lids.

The large box kōji method employs boxes with a capacity for 15kg of kōji, and differs from the room lid production method not only by box size, but also by temperature control strategy. It is an expanded method of the floor kōji method, though with larger boxes, and the rice layer spreading technique is carried out in subdivisions allowing for effective, easy temperature control.

Steamed rice is mixed and piled higher to one side of the box. A thick layer of developing kōji located on one side, gradually thins out over time to widen the heat dissipation surface and make it easier to control the temperature. Overall, the operation process is very simple and the reproducibility of kōji production is high. Owing to the relative ease of operation, training new engineers to master the method is faster than standard box kōji methods which is an added benefit.

Large box kōji methodology aims to produce kōji over a large area on a shelf, which differs from the multi-level box stacking concept of the small box/room lid method.

Photo: When the developing kōji malt is ready to be unraveled, it is mixed

and portioned out into kōji boxes.

This commences the latter period known as the “shelf period”.

(6:50am, January 31, 2021)

And this is how kōji production has evolved over time. The pioneering bed kōji method was replaced by the room lid method, only to then make a comeback as the most popular technique. Later still, machine-driven, mechanical production was developed allowing for larger scale production and was looking to phase out the labor-intensive lid and box methods, however with view to achieving the ultimate in sake quality, an increasing number of brewers are returning to these older styles of kōji making, because at the end of the day, machines can't compete with the skill and love behind the best hand-crafted kōji. The development of new seed kōji breeding methods is progressing, and efforts regarding yeast and kōji development are bearing fruit.

The Kōji Room

Next, let’s talk about the "kōji room", the dedicated facility used to produce kōji malt during the colder months.

First, a word on this room’s requirements. A kōji room must:

(1) have insulation and be kept warm,

(2) be maintained at 30°C using a heat source and a temperature monitoring and adjustment system, and

(3) be furnished with a skylight ventilation system.

Additionally, the room should contain necessary furnishings and equipment such as a kōji box, floor, shelves, and a mixing device that suits the given purpose. Ventilation devices called skylights are for ventilation purposes only and cannot be used to adjust humidity. If air outside the room is moist, humidity inside the kōji room will not differ.

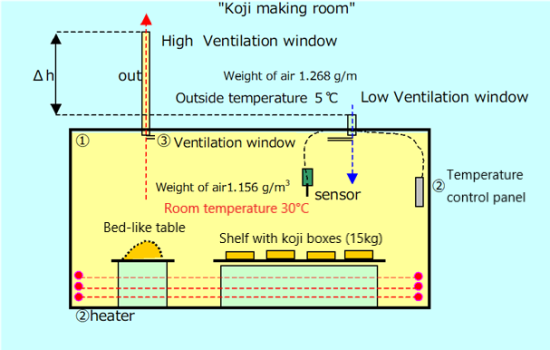

Basic schematic of a Koji Room

Next, a word on room design.

(1) Kōji room design criteria:

(i) White rice handling amount (kōji production capacity) 1.8kg/m3 --- or volume equivalent

(ii) Room height: 2.2m is the standard.

(2) Kōji handling weight per area for (i) bed and (ii) shelf are each 18.75 kg/m2

(3) Bed and shelf combined upper surface area is by standard 40% of total floor surface area

The structure of the kōji room is very simple. During the winter/cold season when temperatures average about 5°C, a partition wall will be installed inside the brewery for insulation, and the room will be heated to, and maintained at 30°C.

Kōji is an aerobic filamentous fungus and in order to propagate it on steamed rice during winter, it is necessary to provide both a sufficient amount of fresh (air) oxygen in addition to the warm temperature provided by the room. For this reason, the warehouse needs to equip a ventilation port called a "skylight". The room's ventilation system constantly cycles fresh air into the room, and the setup includes a flue with a pair of outlets for the air inside the room, and a shutter (sliding door) that can adjust the amount of air intake.

There are two methods for air ventilation: natural and forced. This is the natural ventilation method adopted by Matsumoto Sake Brewery.

Naturally, the specific gravity (density) of the outside air at 5°C and the indoor air heated to 30°C in winter are different. Air from outside flows into the room via the flue and is warmed in the room. With warming, the air increases in volume, becoming less dense. As a result, the air in the room is discharged to the outside. The temperature difference between indoors and outdoors is an important factor in this air flow.

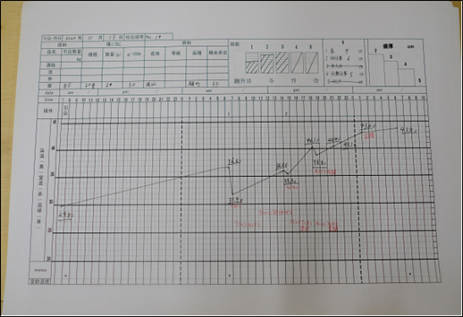

Temperature progress record book: indispensable in kōji making (March 6, 2021)

The difference between the outside temperature and the indoor temperature is represented by Δt, the height difference of the airway is represented by Δh. The amount of air that is taken in is adjusted by the degree of opening and closing of the shutter (the skylight ventilation port).

To ensure that the outside and inside temperatures are at 5°C and 30°C respectively, that there's a supply of fresh oxygen, and that moisture generated from the malt production process is sufficiently eliminated, a Δh of 2-3 m is required (the exact height is adjusted at the operation site in winter).

To maintain this condition, a heat source and a control mechanism are required. In the past, the main heating method employed a certain type of hotbed solution, but these days the use of panel heaters have become safe and popular. The amount of heat required for heating is determined after knowing the amount of steamed rice, the capacity of the koji room and the Δt between the outside air and the insulated air of the room.

Tools used to make kōji (March 6, 2021)

As long as the ventilation port can be opened to about 3cm and the room is maintained at 30C, the ideal conditions can be met. Generally, hotbed wires and panel heaters are single-phase 200V, 500W. In a general brewery, when wiring from a three-phase power line (200V), the number of heaters installed should be a multiple of three. At Matsumoto Sake Brewery, the heat source in the kōji room is 8m in width, 12m in length, and 2.4m in height.

It almost goes without saying, but natural ventilation takes place when air moves between a room and its exterior, owing to a difference between their respective ambient temperatures (and hence air densities). As such, the diminishing difference in indoor and outdoor ambient temperatures which is expected with the start of spring, autumn and summer, lowers natural ventilation to a point that adequate oxygen supply for kōji growth can not be attained.

Photo: The koshiki (rice steaming vat) after taking out the steamed rice

(8:15am, February 26, 2021)

The sake brewery operates in the cold winter months, and the brewery floor is alive with all its varied production processes taking place in harmony, imparting an atmosphere of wonder. The air and water in the rice washing room is a chill 10°C. A moderate temperature of 15°C is required to store the washed rice, and if too cold, the quality of the steamed rice will be impacted. Upon taking out freshly steamed rice at the steaming facility, the worker's skin is exposed to vapor of considerable heat (40°C and 90% humidity). The ventilation fans works vigorously to cycle the steam out of the brewery. Elsewhere, a cooler endeavors to cool down steamed rice to approximately 10°C. Meanwhile, the inside of the kōji room (30°C/30% humidity), is so hot and dry, one would not believe it is winter outside. Well water drawn at 18°C is cooled in a cooler at 3°C. Within the wooden walls of the sake brewery in winter, there exists cold areas, hot and dry areas and hot and intensely humid areas all forming a whole ecosystem of sorts, with the purpose of producing the best sake product possible. At present, it is widely believed to be impossible to reproduce the optimum sake brewing environment through artificial means in summer climes.

COLUMNEssay

Essay

Scenery from the sake brewery - 010 A room for kōji malt

Monthly photo essay on Japanese sake brewing by Mr. Keiichiro Katsuki, a Japanese sake brewing expert.

Please refer to episode 001 for more information on the author.